The period from 1918-1920 marked a watershed like few others. In this short span of time, World War I ground to a halt; four major European and Middle Eastern empires collapsed; Russia established the world’s first communist state; India, Korea, China, and Egypt rose up against imperial domination; and Allied statesmen at the Paris Peace Conference established the first standing world government—the League of Nations—intended to oversee the development of a just and interdependent global order.

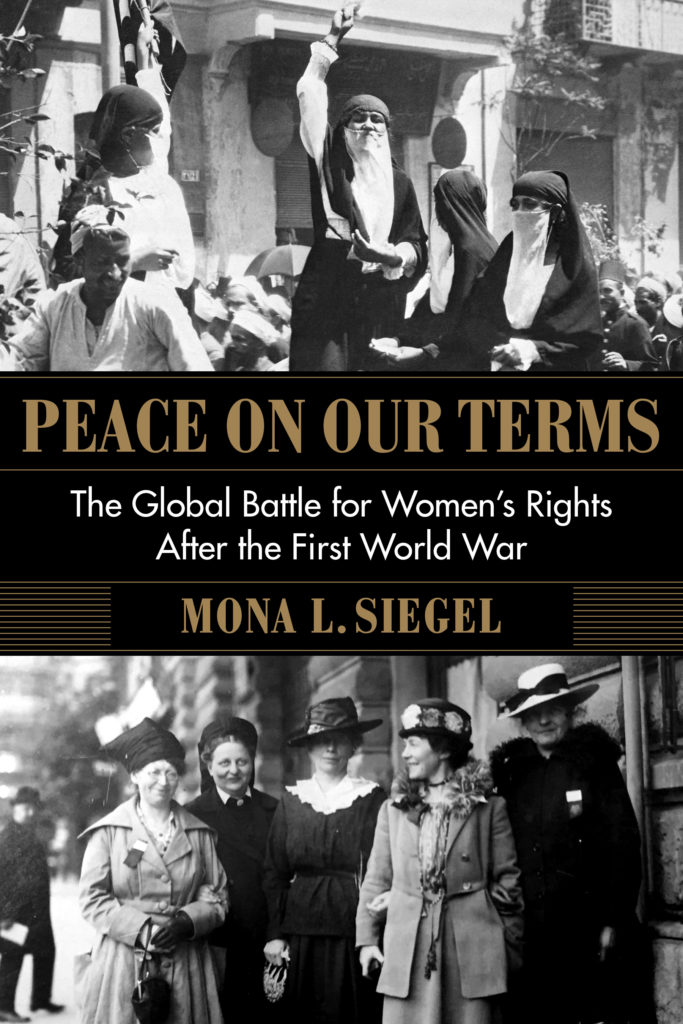

In my new book, Peace on Our Terms: The Global Battle for Women’s Rights After the First World War, I argue that this same period witnessed another momentous and long-ignored historical development: the emergence of global feminism. In the critical year of 1919, dozens of female activists from Europe, the Middle East, North America, and Asia stepped boldly onto the international stage to insist that a stable, peaceful, and democratic world order could not be built without women’s active collaboration.

The women featured in Peace on Our Terms were all catalyzed by the end of World War I and the Paris Peace Conference. By January 1919, Western suffrage leaders had already begun to descend on the French capital to demand recognition of women’s rights as an integral component of the peace settlement. Pan-African feminists arrived shortly thereafter, denouncing the racial violence that oppressed and terrorized people of color, including women, around the world. Chinese bomb-smuggler-turned-feminist-law-student Soumay Tcheng came to Paris in 1919 as well, in her case as an appointed member of China’s peace delegation: the only woman in the world to enjoy such official diplomatic credentials.

Feminist activism was not restricted to France. In March 1919, Egyptian nationalist and nascent feminist Huda Shaarawi led women in Cairo in defiant protest against British colonialism and in defense of Egypt’s right to establish a democratic state. Two months later, pacifist feminists from recently warring nations congregated in neutral Switzerland, embraced their former enemies, and denounced the Versailles Treaty as a vindictive peace. Before year’s end, labor feminists traveled from Paris to Washington, D.C. to insist that the newly formed International Labor Organization address working women’s right to industrial justice and gender equality.

In 1919, in the name of peace, democracy, and social justice, women traversed oceans and continents. They organized mass meetings. They drafted women’s charters and international labor standards. They marched in the streets.

And they did it all in the midst of a global pandemic. From early 1918 through the summer of the following year, tens of millions of people across the globe succumbed to the Spanish flu, one of the deadliest viral outbreaks in human history.

Unsurprisingly, Spanish flu influenced women’s activism and affected their work. The pandemic reached Egypt in the fall of 1918, taking the life of Malak Hifni Nasif, a pathbreaking women’s rights advocate. As her funeral procession passed through Cairo, Nasif’s distraught friend, Huda Shaarawi, cast aside harem proscriptions to join the cortège. Soon after, Shaarawi gave her first public speech in tribute to Nasif’s legacy, thus initiating a life-long commitment to feminist activism. Scottish feminist and labor leader Mary Macarthur lost her beloved husband to the disease several months later. Seeking solace in activism, Macarthur would travel to Washington for the 1919 International Labor Conference with her young daughter in tow to advocate for the rights of working women.

The Spanish flu struck in Paris as well. In March 1919, Western suffragists pressing a women’s rights agenda with the peacemakers were finally accorded permission to address the League of Nations Commission. The long-awaited summons to testify, however, took weeks to materialize because the chair of the Commission, American President Woodrow Wilson, was direly ill with what many now suspect was the Spanish flu. When the women did finally appear on April 10, they extracted a promise from Wilson that all League positions would be open to men and women on an equal basis, a principle enshrined in Article 7 of the League Covenant.

Overall, however, while the tragedy of Spanish flu touched women’s personal lives, it seldom impeded their public work. Most feminists were surprisingly quiet about the deadly pandemic. Many undertook risky journeys over long distances despite the ebb and flow of the disease. Looking back a century later—as the world hunkers down in the midst of the deadly coronavirus pandemic of 2019-2020—it is easy to condemn women’s decisions as shortsighted or reckless. Viewed in context, they are more understandable.

From 1918 to 1919, war and peacemaking were global leaders’ top priority. During both the first and second waves of the Spanish flu in 1918, belligerent governments deliberately withheld information about the disease to prevent interruption to war economies. Both in 1918 and in 1919, heads-of-state including British Prime Minister David Lloyd George and American President Woodrow Wilson remained silent on the topic and hid their own severe symptoms from public view. Feminists, like most people in 1918-1919, functioned with imperfect knowledge about the scope of the pandemic or how to address it.

But even if feminists never considered curbing their activism in the face of the Spanish flu pandemic, for many of them, public health was, and had long been, a matter of serious concern. Disease and hunger were issues they understood intimately and could speak about authoritatively. In 1919, they used their rare moment in the global spotlight, in part, to try to persuade male political leaders to recognize the direct link between public health and global security.

Women across the world cared for the sick in their families and communities. Egyptian feminist Huda Shaarawi’s first major philanthropic project was to establish a clinic for poor women and children in Cairo. Many pioneering female doctors, nurses, and medical workers became devoted feminists. In 1919, American Florence Jaffray Harriman, director of the Red Cross Women’s Motor Corps during World War I, participated in women’s feminist lobbying efforts in Paris, as did some of the first female doctors licensed in France. Dr. Aletta Jacobs, the first female doctor in the Netherlands, helped organize the 1919 International Congress of Women in Zurich, Switzerland.

From their collective experience, women forwarded specific recommendations. Speaking for Western feminists before the League of Nations Commission in 1919, Dr. Nicole Girard-Mangin—a specialist in contagious disease and the first female doctor to serve in the French Army—called on the new world government to establish a standing global Public Health Office. Article 23 of the League Covenant, which pledged the new world government to “take steps in matters of international concern for the prevention and control of disease,” fell far short of this recommendation; nonetheless, over time, successive international bodies would coalesce into the World Health Organization, which provides critical leadership in addressing global health crises, including the coronavirus pandemic today.

Work conditions also figured into feminists’ understanding of public health. On the advice of French doctors Clotilde Mulon and Lasthénie Thuillier-Landry, feminists pressed the peacemakers to declare the health of working mothers to be a global priority. Labor feminists continued to build the case, convincing the First International Labor Conference to adopt the Maternity Protection Convention of 1919, a pathbreaking global standard that called for a minimum of twelve weeks paid maternity leave.

Pacifist feminists who gathered in Switzerland in May 1919 had even more to say on the subject of global public health. Of immediate concern was the famine seizing the vanquished states of Central Europe: a human catastrophe personified by Austrian feminist Leopoldine Kulke, who arrived in Zurich from Vienna starving and ill. In its first official act, the International Congress of Women sent a searing telegram to Paris condemning the ongoing food blockade of the defeated Central Powers as a “disgrace to civilization.”

The feminists in Zurich went further. They called on global leaders to build “an international organization for the purposes of peace” capable of guaranteeing that “the resources of the world” are “made available for the relief of the peoples of all countries from famine and pestilence.” In their eyes, only by ensuring a fairer distribution of the world’s resources, including food and wealth, would the world’s powers achieve some measure of global security.

Today, in the midst of the coronavirus pandemic of 2019-2020, feminist policy experts are echoing many of these same themes. Madeleine Reese—Secretary General of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, the organization born of the 1919 Zurich Congress—reminds us that expensive military buildups do little to address the structures that leave populations vulnerable to disease and do much to exasperate global inequalities that deepen health crises. Sanam Naraghi Anderlini, Director of the Centre for Women, Peace and Security at the London School of Economics, has similarly asserted that public health is a matter of global security and that women, who have long called for prioritizing health and social welfare in global policymaking, are needed as full partners in mitigating the current crisis and in plotting a course forward.

Are global leaders more likely to head women’s warnings in 2020 than were their counterparts a century ago? Making peace and ending pandemics demand the full breadth of human knowledge and experience. Both require a sustained investment in public health. Foreign policy that ignores social welfare imperils us all. Feminists pleaded this case in 1919. Their advice remains no less pertinent today.

Mona Siegel is a Professor of History at Sacramento State.

She tweets @mona_siegel