On her last day at the Centre, Siobhan Morris reflects on her experience of advising on, and conducting, public engagement as part of a research project.

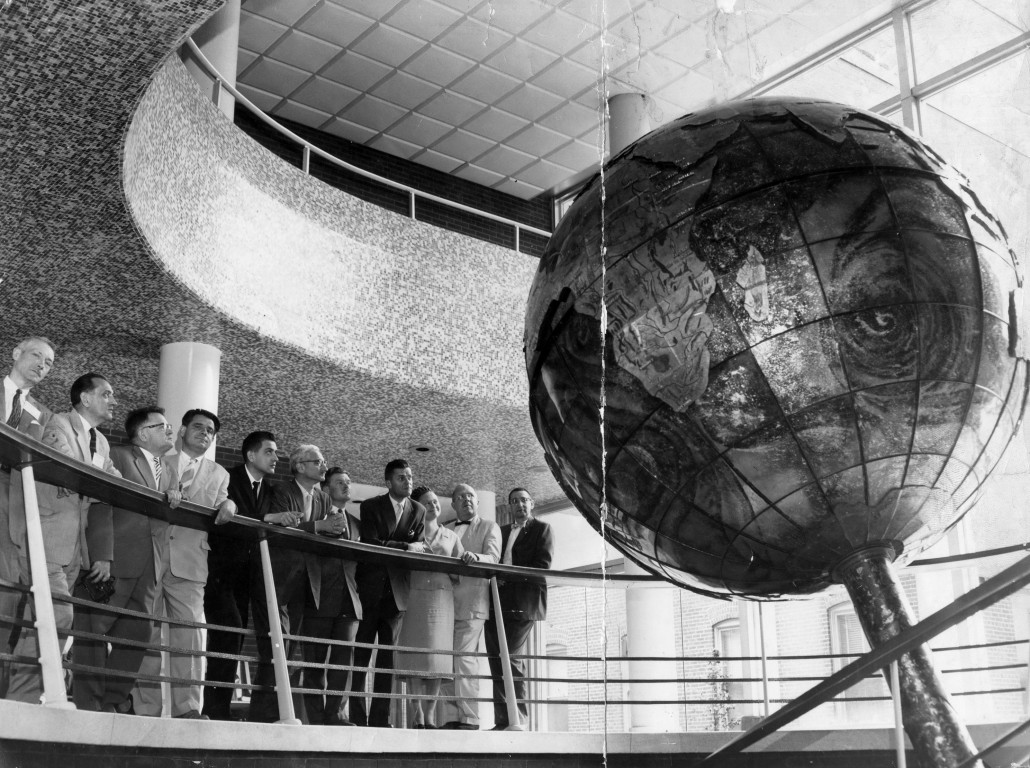

For the last year I’ve had two roles: Manager of the Centre for the Study of Internationalism, and Public Engagement and Events Coordinator for The Reluctant Internationalists project, both based in the department of History, Classics and Archaeology at Birkbeck College. The project, led by Dr Jessica Reinisch, studied international organisations and movements in twentieth-century Europe through the lens of public health, medicine and medical science. Over a period of four years, the research group examined the history of international collaboration of medical professionals, relief workers, soldiers, politicians and local officials (among others) in Europe’s long twentieth century. The two were connected in that the conversations begun during the project led to the establishment of the Centre for the Study of Internationalism.

The project was funded by Dr Reinisch’s Wellcome Trust Investigator Award, with a subsequent award in summer 2016 of a Wellcome Trust Public Engagement Grant, enabling the project to recruit a Public Engagement and Events Coordinator. The post offered an exciting opportunity to work on the project’s existing public engagement activities as well as devise new means of transmitting the project’s research and findings to non-academic audiences. We thought a lot about what the strengths and limitations of ‘public engagement’ were, and which ‘publics’ we wanted to engage with. The programme of activities sought to engage young people in the history of internationalism and foster conversations with school teachers and their pupils with the ultimate aim to influence how history was being taught in schools. History, and the history of internationalism in particular, is a potent tool for teaching children how to shape and dissect arguments, distinguish between types of evidence, and to think critically about contemporary debates. The project therefore aimed to provide teachers with resources and support to bring the history of internationalism into the classroom and to equip pupils with tools for understanding the world they live in.

The project was funded by Dr Reinisch’s Wellcome Trust Investigator Award, with a subsequent award in summer 2016 of a Wellcome Trust Public Engagement Grant, enabling the project to recruit a Public Engagement and Events Coordinator. The post offered an exciting opportunity to work on the project’s existing public engagement activities as well as devise new means of transmitting the project’s research and findings to non-academic audiences. We thought a lot about what the strengths and limitations of ‘public engagement’ were, and which ‘publics’ we wanted to engage with. The programme of activities sought to engage young people in the history of internationalism and foster conversations with school teachers and their pupils with the ultimate aim to influence how history was being taught in schools. History, and the history of internationalism in particular, is a potent tool for teaching children how to shape and dissect arguments, distinguish between types of evidence, and to think critically about contemporary debates. The project therefore aimed to provide teachers with resources and support to bring the history of internationalism into the classroom and to equip pupils with tools for understanding the world they live in.

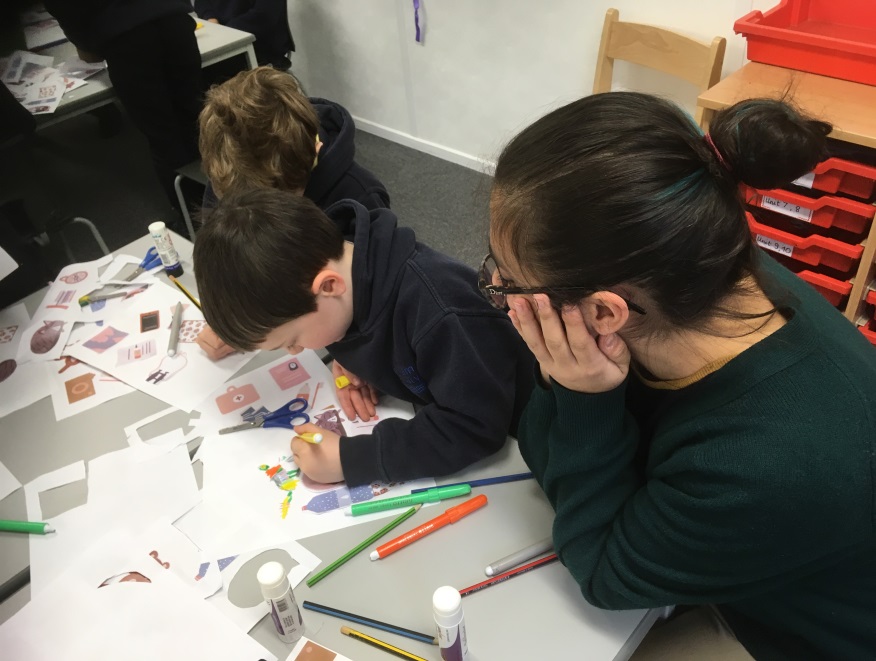

To meet this goal, the project organised workshops exploring refugees in children’s literature; established the Birkbeck History Teachers Network to provide a forum for secondary school teachers who are current or former students of Birkbeck and their colleagues; and ran a teacher fellowship programme in conjunction with the Historical Association entitled, ‘The Cold War in the Classroom’, which provided teachers the opportunity to draw on the expertise of the project’s historians, to exchange ideas about teaching practice, and to work towards creating original learning resources. In addition, the project has been developing an online teaching companion which features textbook-style chapters and a range of primary sources designed for exploring the history of internationalism in the classroom.

An undoubted highlight of our activities for me, however, was the project’s collaboration with the children’s author/illustrator Francesca Sanna. During her time at Birkbeck, Francesca and the group explored how to get children to think about internationalism, migration, violence, and empathy with others – discussing different historical contexts and refugee policies as part of preparations for her book project, Me & My Fear (to be published with Flying Eye Books in September). Working with Francesca was truly inspiring and I feel incredibly lucky to have had the opportunity to witness the children’s book take shape. I was also afforded time to interview Francesca about her work and along with other members of the project I accompanied her on workshops with over 260 children at London primary schools. It was enormously heart-warming to see both teachers and pupils eager to engage with the themes raised by Francesca’s work, and that of the Centre for the Study of Internationalism, on migration, war, travel, fear of the unknown, and empathy with others. These activities led to the project’s work with Francesca being awarded Best Collaboration at Birkbeck’s inaugural Public Engagement Awards in March, which was a wonderful recognition of the project’s activities and approach to public engagement. I’m delighted that this collaboration is continuing under the guise of the Centre and look forward to hearing more about events to mark the official launch of the book later this year.

Reflecting back on my time at Birkbeck has also impressed on me how unusual my role has been in cutting across the demarcations that often exist between centralised public engagement departments and individual research projects. Being embedded within The Reluctant Internationalists and Centre for the Study of Internationalism teams, working directly with the project’s academics and visiting fellows, has been invaluable. This allowed me to gain understanding of the research being undertaken and enabled me to find ways to transmit research findings and tailor communications to non-academic audiences. I also believe having a dedicated public engagement post, such as mine, directly funded as part of a research project has been enormously beneficial in ensuring that public engagement was not viewed as a burdensome ‘add-on’ to the project. For public engagement to be truly meaningful and beneficial, engagement activities must be regarded as an integrated part of the research process. Public engagement for public engagement’s sake is never beneficial to either party – neither academic nor public.

Similarly, the role has also prompted me to consider the definitions of public engagement employed by different institutions and how this might affect relationships between researchers and professional support staff. As Birkbeck’s public engagement manager Mary-Clare Hallsworth recently noted, ‘the language we use about what we really mean by public engagement is not universal and differs significantly by discipline.’ Therefore, attempting to impose strict definitions on public engagement and assign tags to engagement activities can be problematic. I have noted a disconnect at times between the language used by academics and researchers and that spoken by public engagement professionals. Having dedicated positions that embed public engagement support within research teams can act to bridge divides between researchers, departments, and central offices.

Integrated public engagement undoubtedly has the potential to enable academic research to make a lasting difference in communities and, as The Reluctant Internationalists project has sought to achieve with its work with teachers and pupils, to promote critical thinking and shape outlooks. It has been a privilege to be a part of.