The latest in our Spotlight series highlighting the breadth of research being conducted by the Centre’s members features Simon Jackson, Lecturer in Modern Middle Eastern History and Director of the Centre for Modern and Contemporary History at the University of Birmingham.

What are you currently working on?

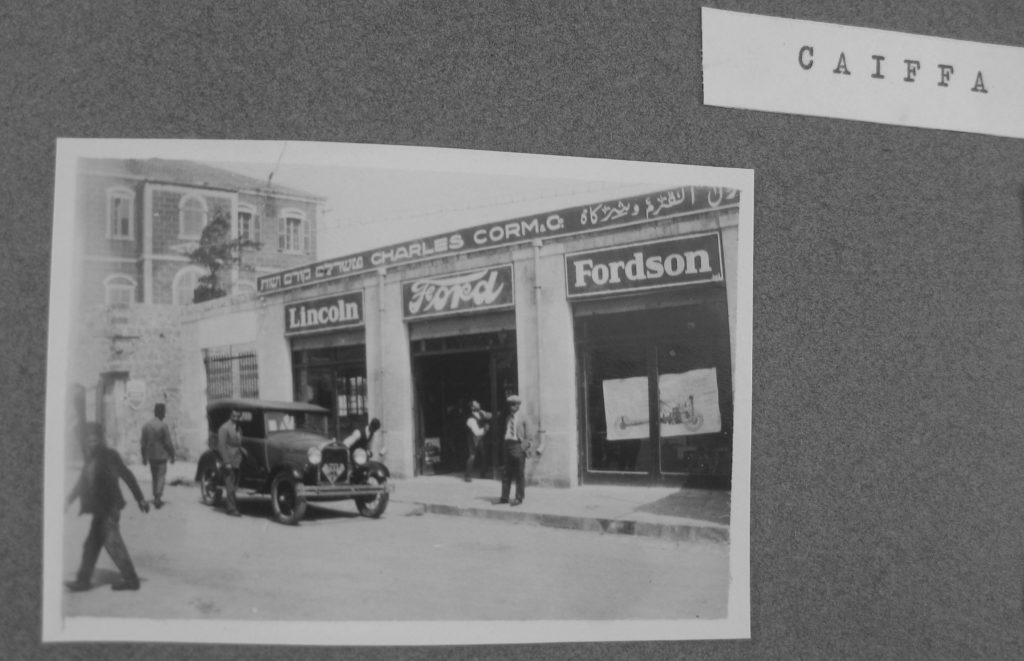

I’m currently finishing a book project titled Mandatory Development: French Colonial Empire, Capitalism and the Politics of the Economy after World War One. It focuses on the political economy of the French Mandate in Syria-Lebanon after the First World War. The book examines the interface of imperialism and capitalism through cases such as boycotts of foreign-owned tramways in Beirut, the story of the man who obtained the sole right to import and distribute Ford cars in the Levant, how France ended up committing to the Syrian Mandate in the aftermath of the war, and the role of diaspora humanitarianism and petitioning of the League of Nations in the shaping of the Mandate system. In the accompanying image you can see a Ford showroom in Mandate-era Haifa – it’s a shot that in itself I think re-casts and diversifies our understanding of what Fordism was, taking us way beyond Detroit and Dagenham.

I’ve also co-edited a volume with Alanna O’Malley that’s about to come out in July 2018 and should, I hope, be of interest to the Centre’s adherents. Entitled The Institution of International Order: From the League of Nations to the United Nations the volume builds on the huge wave of recent scholarship on the League and UN, treats the two institutions’ interconnections in a more systematic way than is often the case, and appraises their internationalism in a global and multi-local context. For example, José Antonio Sánchez Román’s chapter looks at the League’s economic meetings on taxation and navigation, illuminating alliances on these issues between Latin American and post-Ottoman Middle Eastern or post-Habsburg Central European states. He tells the story using the classic Geneva archive of the League, but also primary sources from Brazil and Argentina, which is very much the approach the whole volume advocates for in the field of international history. You can find out more about the volume on Twitter, where it has its own account @lon2un.

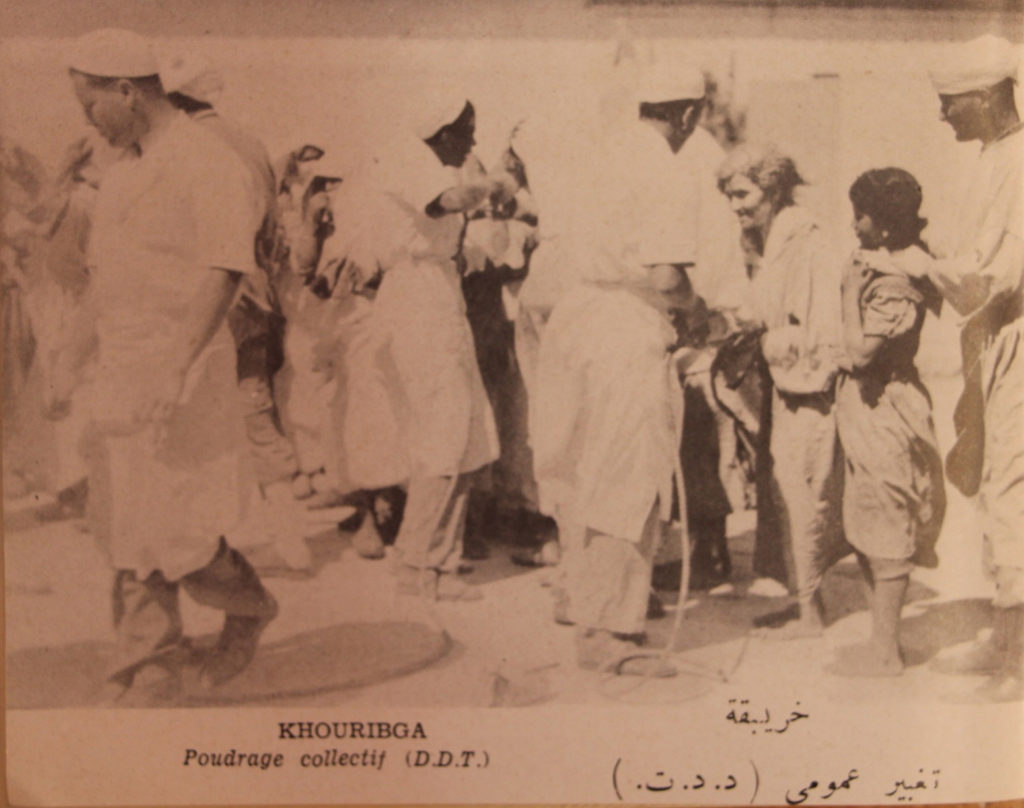

Finally, I have a new project on the go, which looks at phosphate mining in French colonial North Africa across the twentieth century. Phosphate is one of the key elements of modern fertiliser-driven agriculture and therefore indispensable to today’s global food system. Building on great work by a range of current scholars I want to show how that system has its roots not just in the anti-Communist ‘Green Revolution’ of the Cold War, but in the colonial world order.

What have been some of the key findings of your research so far?

Mandatory Development argues that French Mandate rule is a key part of the global story of development in the twentieth century, and that that story has roots in the period after the First World War, rather than after the 1945. It also argues that (French) colonial empire has to be grasped in global perspective, whether in terms of the role of capitalist organisations like Ford, or in terms of the role of diaspora groups and international organisations.

How does ‘internationalism’ feature in your research?

Internationalism got into my work through the League of Nations, which was my portal into the historiography and archives of internationalism at large. Latterly, organisations like the International Committee of the Red Cross, the Red Crescent or the International Agricultural Institute have provided institutional anchors for my research, but I’ve increasingly been drawn to thinking about internationalism in terms of capitalist organisations, first and foremost Ford. I think that the nexus of corporate entities and international organisations is a highly promising site for research, one that can bring together economic and business historians with international historians, areas studies scholars and historians of international law. Tehila Sasson’s recent work on Nestlé and the FAO is a terrific example of how this can work well.

Can you explain how your work challenges, differs from, or complements, other work in your field?

Broadly speaking, my work challenges historians of colonial empire, particularly in the French case, to think more globally about the networks and circulations that shaped imperial rule, and to get out from under the binary relationship of metropole and colony a bit more. I also hope to challenge economic historians at large, and notably historians of development and commodities, to take the culture of empire and the cultural history of political-economy more seriously.

Finally, I hope that my work on Ford, but also on phosphate, moves discussion of the big dynamics they represent, (Fordism and agro-chemical food production), away from a focus on histories of Europe or North America in isolation to a more inter-connected and global approach. I’m involved in a British Academy-sponsored network called Commodities of Empire, and I’ve found a lot of the work done through the network has prompted me to think about commodities and materiality in helpful ways.

What has been your proudest achievement to date?

On the research side, in 2016 I organised a workshop at Birmingham on ‘The Global Middle East in the Age of Speed’ that brought together scholars from a varied set of fields and contexts. I felt it worked out well, with collaborative exchanges across various lines, which is something I think is important and was proud of. I’m now working on editing a section of Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East that brings together some of the contributions from the workshop.

I also worked with A. Dirk Moses on a recent dossier in Humanity that looks at transformative occupation in the modern Middle East – I’m very proud of that and to have had the chance to work with Dirk and edit work by the likes of Nida Alahmad, Tareq Baconi, and others.

On the teaching side, I’m very proud of my students’ achievements: at Birmingham I’ve had a chance to work with some wonderful PhD students doing ground-breaking work – for instance Eliana Hadjisavvas’s recent dissertation on Jewish refugees interned in Cyprus after the Second World War is an extraordinary project which will completely transform our understanding of the post-war moment.

Are there any aspects of your work that could be particularly relevant to scholars from other fields or practitioners in other areas?

I hope that my work on the colonial history of development finds some readers in Development studies more generally and perhaps among practitioners seeking a more historical understanding of their field. I also think that The Institution of International Order: From the League of Nations to the United Nations will interest International Relations and Politics scholars.

Where do you see your work going next?

I’m going to work more on the history of agriculture, phosphate and food politics, which I think will take me more to Morocco and Tunisia and Algeria to learn about the social history of mining. For my third book I’d like to write on French environmental politics in the 1970s and 1980s and towards that I’ve recently been reading about René Dumont, a fascinating figure who was the Green candidate in the 1974 French presidential election and an agronomist whose career traversed the twentieth century.

What would you like to ask the next person to be featured in this ‘spotlight’ series?

Well, Stephen Legg asked whether the centenary of the Versailles conference and the founding of the League will create a new appetite and more public attention for thinking about internationalism, and my answer is that I hope so, but also that I think scholars need to work hard to move the focus beyond the usual suspects and topics – Keynes, Wilson, reparations etc. – and look beyond Europe more. One of the best things about the WW1 centenary has been the concerted push to diversify the public understanding of the war, and I think the same is needed going forward.

I would ask the next person in the spotlight: in what ways can future research on internationalism best foster collaborative and collective forms of inquiry among scholars who are often encouraged to pursue individual projects?