In the latest instalment of our Spotlight blog series highlighting the breadth of research being conducted by the Centre’s members, we focus on David Brydan, Lecturer in Modern European History at Birkbeck College, University of London.

What are you currently working on?

I’m currently finishing the final transcript for my book, Franco’s Internationalists, which is to be published by Oxford University Press next year. The book tells the story of the experts who tried to promote the idea that Franco’s Spain was a ‘social state’, dedicated to welfare, social progress and humanitarianism. It follows their involvement in different types of international organisations and networks during the 1940s and 1950s, from Nazi Germany and the ‘New European Order’ during the Second World War, to the WHO and other forums for international cooperation after it.

What have been some of the key findings of your research so far?

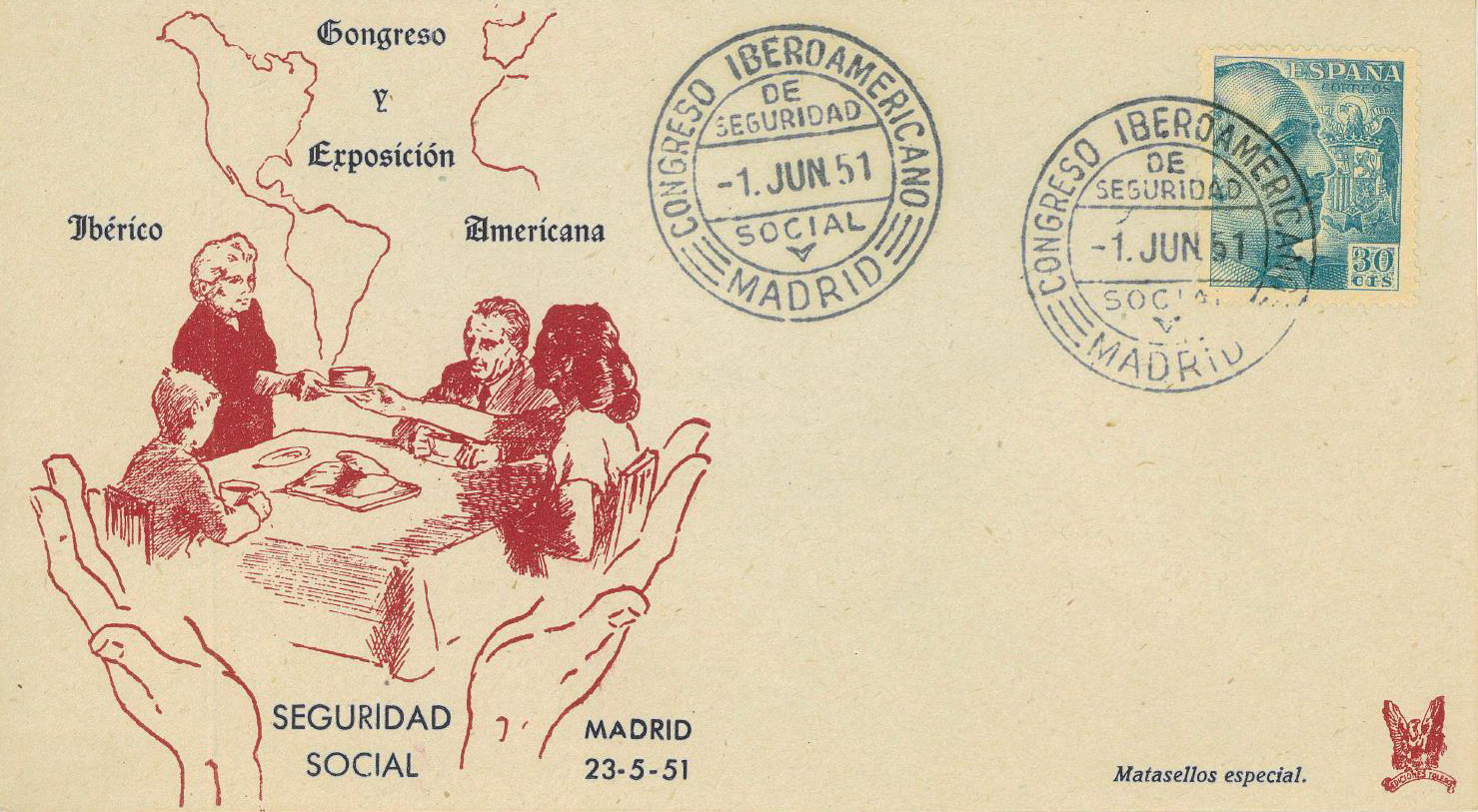

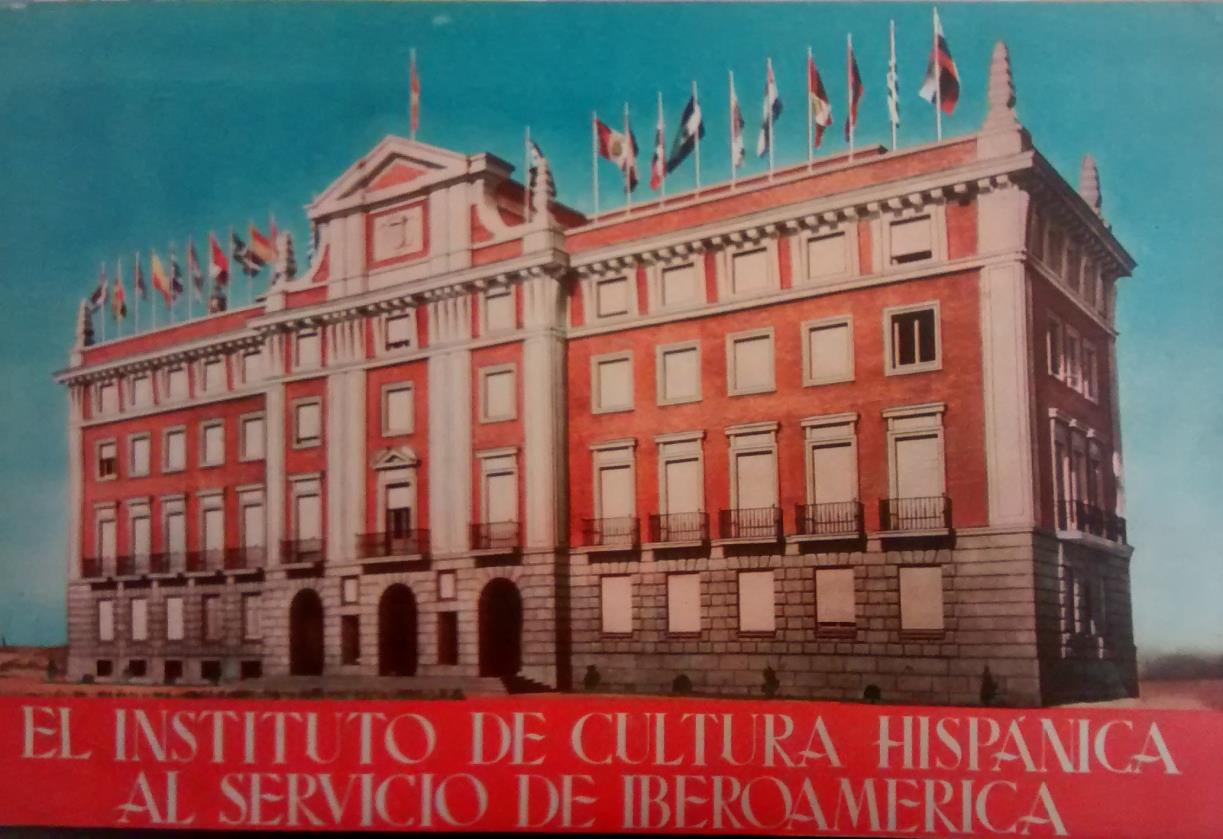

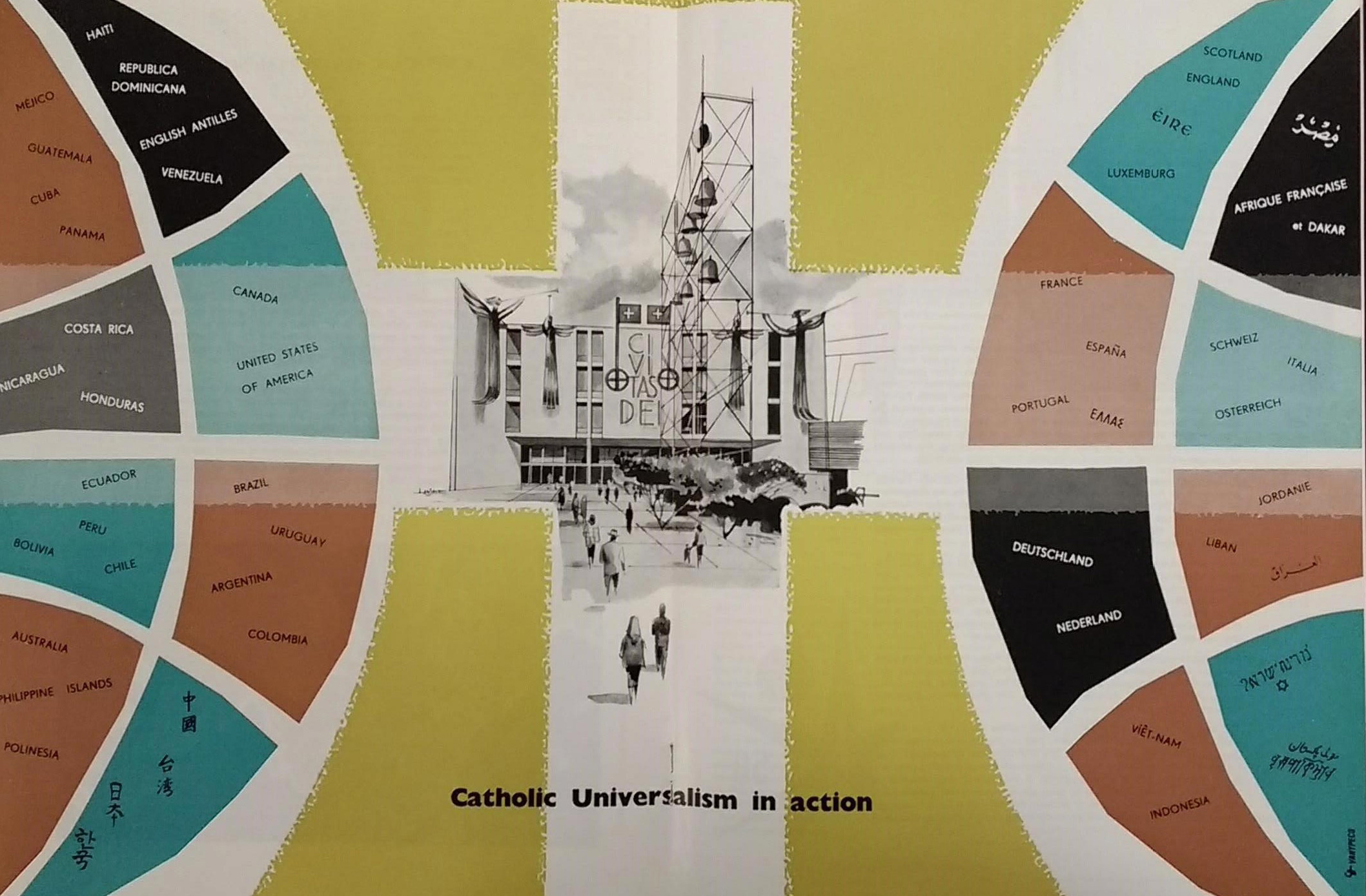

From the perspective of Spanish history, one of the key discoveries has been how interested Francoist elites were in international cooperation during the early decades of the regime. The international history of Franco’s Spain has traditionally painted this period as one of isolation, when autarkic economic policies were combined with a belligerent attitude towards other states and absence from key international organisations, only changing in the 1950s with economic liberalisation and Spain’s partial integration into the international community in the context of the Cold War. But my research shows how Francoist elites worked hard to try to integrate Spain into international organisations and networks right from the end of the Spanish Civil War. In part that involved adapting to the shifting international environment, initially the new European networks being created by Nazi Germany, and then the UN systems which emerged after 1945. But it also involved attempts to promote new international networks and communities more aligned with Francoist ideas and values, from the idea of an ‘Ibero-American’ community united by shared history, religion, and culture, to the diverse forms of Catholic internationalism which played a prominent role in the post-war world.

From the perspective of Spanish history, one of the key discoveries has been how interested Francoist elites were in international cooperation during the early decades of the regime. The international history of Franco’s Spain has traditionally painted this period as one of isolation, when autarkic economic policies were combined with a belligerent attitude towards other states and absence from key international organisations, only changing in the 1950s with economic liberalisation and Spain’s partial integration into the international community in the context of the Cold War. But my research shows how Francoist elites worked hard to try to integrate Spain into international organisations and networks right from the end of the Spanish Civil War. In part that involved adapting to the shifting international environment, initially the new European networks being created by Nazi Germany, and then the UN systems which emerged after 1945. But it also involved attempts to promote new international networks and communities more aligned with Francoist ideas and values, from the idea of an ‘Ibero-American’ community united by shared history, religion, and culture, to the diverse forms of Catholic internationalism which played a prominent role in the post-war world.

How does ‘internationalism’ feature in your research?

My research seeks to uncover what it meant for nationalists to think and act internationally during the middle of the twentieth century. Despite the recent works which have highlighted the diverse history of internationalism, it is still too often associated with liberal values and with mainstream international organisations, or sometimes with socialist and communist movements. But we cannot ignore the fact that international projects and ideas were also embraced by nationalists, fascists, and conservatives. My work seeks to uncover the diverse range of international projects which competed and interacted with each other during the period, many of them built around imperial or neo-imperial projects, or around ties of religion, language, or ideology.

Can you explain how your work challenges, differs from, or complements, other work in your field?

I think the difference with my work is one of perspective. There are lots of studies of international movements or organisations written from the point of view of Britain, the United States and other liberal western states. But this history looks very different if we shift the perspective from which we approach it. Elidor Mëhilli’s recent book, for example, provides a completely new take on post-war socialist internationalism by examining it through the lens of Albania. My research tries to do something similar, but from the opposite end of the political spectrum, by using Franco’s Spain to explore the history of internationalism from the perspective of the authoritarian nationalist right. Spain is so often absent from international and European histories of this period because it is such an outlier, and it’s hard to work out how it fits with our familiar ideas and chronologies. But if we make the effort to understand what the world looked like from this perspective, or from that of other geographically or ideologically ‘peripheral’ countries, we can gain a much better understanding of the diversity and complexity of the history of internationalism.

What has been the most controversial aspect of your research?

I wouldn’t say it’s controversial necessarily, but it sometimes takes people a while to get their heads around the fact that I’m looking at the histories of internationalism, global health and humanitarianism through the perspective of such a repressive, authoritarian regime. I think there’s still an assumption that these activities just ceased in Spain under the dictatorship – that they ended in 1939 and only started again after the transition to democracy. It’s also a slightly unusual approach to take to the early Francoist period, where historiography is dominated by themes such as repression and state violence. This is an incredibly important body of work, but hopefully my research can contribute to the development of a broad English-language scholarship which integrates Spain into wider developments in European and international history during the period.

What has been your proudest achievement to date?

I’m really just proud to have been able to build a career in academia. I didn’t really enjoy my undergraduate studies and had never thought seriously about a research career. But after nearly a decade in other jobs and a part-time MA at Birkbeck, I decided that an academic career would be the perfect way to combine my love of teaching and history. I knew it would be hard and was always ready at the back of my mind to return to my old career if this didn’t work out. But I managed to pass my PhD, published some articles and got a book contract, and will be taking up a permanent post at King’s College London in a few months time. I’m very proud of all of that, but also grateful to all the people who have helped me to achieve it.

Are there any aspects of your work that could be particularly relevant to scholars from other fields or practitioners in other areas?

I think my work on the relationship between the Franco regime and the UN’s specialised agencies, particularly the WHO, is relevant to political scientists and IR scholars interested in international organisations. And my new project on Christian NGOs and international organisations will, I hope, be relevant to scholars of humanitarianism, particularly those interested in the role of faith and religion in humanitarian work.

Where do you see your work going next?

I’m just starting a new project on the history of Christian internationalism and humanitarianism in the post-war era. It emerged from my previous work on Spanish involvement with international Catholic organisations during the same period. A huge array of international Christian groups, both Catholic and Protestant, sprang up during the middle of the twentieth century. After 1945 they were actively engaged with debates about the new international system and about topics such as peace, development, and human rights. And in many cases they seem to have had a substantial impact on the work of international organisations, and on the international policies adopted by western governments. But in the context of the Cold War they also played an important role in promoting the idea of the West as a spiritual community, united by religious identity and values against the atheistic materialism of the communist world. The project aims to uncover the visions of world order promoted by these Christian internationalists after 1945, but also to investigate their impact on the post-war international system.

In our previous spotlight post, Brigid O’Keeffe posed the question: what practical advice would you give to an early doctoral student who wants to pursue a dissertation topic (no less than an academic career) within the frame of the history of internationalism?

My first piece of advice would be to go for it! It’s an exciting field with lots of great work currently being carried out, but also lots of scope to explore new fields. Aside from that, my main piece of practical advice would be to try to gain at least reading proficiency in as many languages as possible. We struggle with learning foreign languages in the UK and the US, and I suspect it’s partly our monolingualism which has contributed to the traditional emphasis on Anglo-American perspectives within the history of internationalism. But foreign languages are vital if we want to really appreciate the diversity of this field. Even if your work focuses on English-speaking countries or mainstream international organisations where English is a major working language, much of it will involve following ideas and actors as they cross borders. Our language capabilities will always place limits on the research we can do, but the more languages we have the further we can follow these threads of evidence. I am certainly not a natural linguist and I have always found learning foreign languages difficult, but having other languages has definitely benefited my own research and I’m always conscious that expanding my language knowledge will allow me to broaden the scope of my future work.

What would you like to ask the next person to be featured in this ‘spotlight’ series?

There are lots of debates at the moment about the ‘liberal world order’ which supposedly emerged after 1945 and which is now under threat from Trump, Brexit, China, etc. How can we, as scholars of internationalism, contribute to these debates?