The latest post in our Spotlight series highlighting the breadth of research conducted within the Centre and starting dialogues between researchers from different academic disciplines, features Brigid O’Keeffe, Associate Professor of History at Brooklyn College, CUNY.

What are you currently working on?

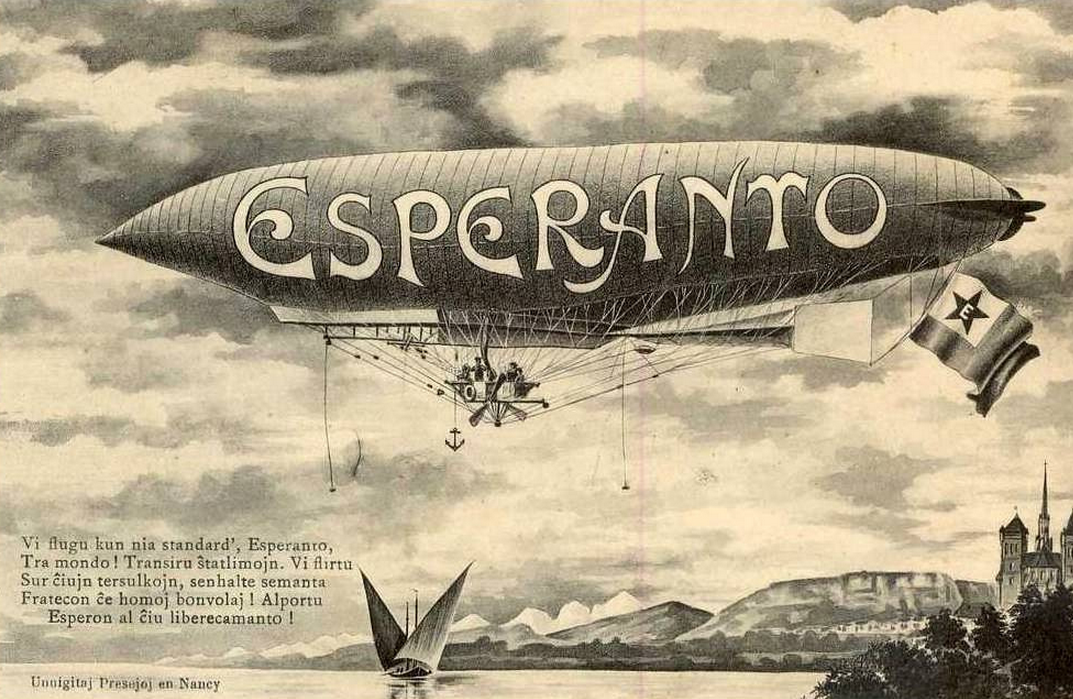

I am currently writing a book on the history of Esperanto and the language politics of internationalism in late imperial Russia and the early Soviet Union. L.L. Zamenhof created the international auxiliary Esperanto to facilitate mutual understanding among the world’s fractured peoples. In 1887, he published his first Esperanto primer from the western borderlands of his native Russian empire, thereby launching what ultimately became a global Esperantist movement. Esperanto inspired a wide variety of political actors in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries— a time when men and women around the world were searching for a workable international language that could facilitate commerce, travel, diplomacy, and the exchange of ideas and expertise. Many Esperantists—Zamenhof among them—looked to the adoption of an international auxiliary language as the key to achieving world peace.

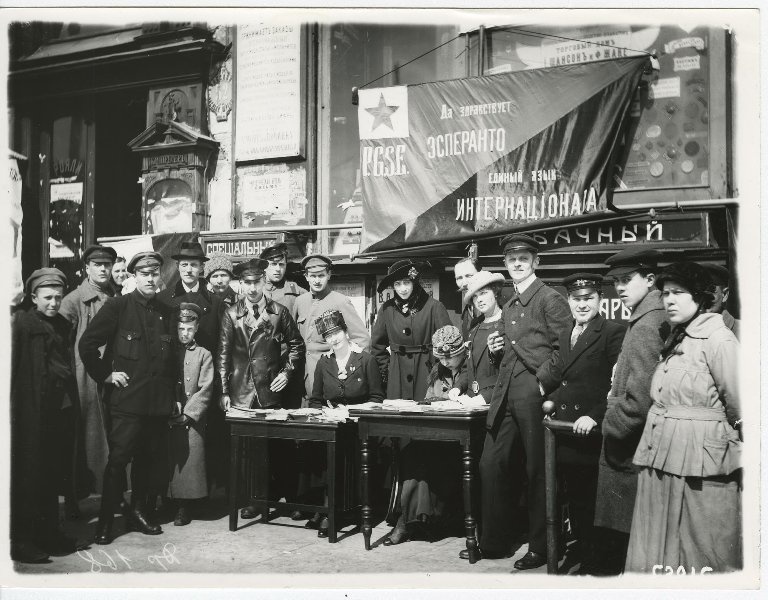

My book explores how men and women in late imperial and early Soviet Russia sought to transcend national and imperial borders in their varied efforts to transform the world using Esperanto. In late imperial Russia, Esperanto drew an increasingly diverse literate Russian public into global campaigns to promote international solidarity, variously conceived. In the wake of the October Revolution, many of Russia’s young Esperantists eagerly pursued partnership with the Bolsheviks. They committed to deploying Esperanto as a tool of international proletarian revolution—a tool, they claimed, that the Comintern could not afford to do without. Esperanto, they insisted, was the distinctly proletarian international language without which the workers of the world could never unite. They promised, too, that Esperanto would crucially aid in the translation and application of the foreign technological expertise that would be required to transform the Soviet Union into an industrial powerhouse during Stalin’s first five-year plans. In the mid-1930s, however, the Stalinist state fatefully deemed Esperanto a language of treason and its promoters – traitors, Trotskyites, and spies.

From its launch in 1887 until Stalin’s devastation of the Esperanto movement during the Great Purges and Terror, Esperanto served ordinary Russians as an international language with which to collaborate and correspond with comrades throughout the world. Esperanto also raised often painful questions about imperial Russia and the early Soviet Union’s role in the world as it brought into stark relief the international politics of language in a self-consciously globalizing age.

How does ‘internationalism’ feature in your research?

I show how Esperantists, as “ordinary” agents of internationalism, sought to invest an international language with the power to transact their ideological goals. On both sides of 1917, Esperantists committed to improving humankind and the world by revolutionizing the politics of language. They sought to create a global citizenry fluent in both an international auxiliary language and shared humanitarian values. On a more personal level, they eagerly reached out to the world, seeking transnational friendships and other partnerships that Esperanto uniquely enabled them to pursue.

Yet these Esperantists never enjoyed the unimaginable luxury of pursuing their internationalist goals free of the restraints imposed upon them by the late tsarist and the early Soviet states. Both the late imperial autocracy and the early Soviet regime were at the very least sceptical (and sometimes downright hostile and repressive) when it came to the Esperantists’ activities, goals, and politics. Tsarist and Bolshevik officials typically dismissed Esperantists as harmless eccentrics, niche enthusiasts, and wild-eyed dreamers. Others, however, regarded Esperantists as threats with the potential to transcend state and ideological borders and to evade the modern techniques of government surveillance and control. While its ardent adepts saw in Esperanto the keys to liberation (political, social, technological, and cultural—and all on a world scale, no less), state authorities in late imperial Russia and the early Soviet Union fatefully saw in Esperanto the potential for borderless subversion. In their varied pursuit of internationalist projects in late imperial and early Soviet Russia, Esperantists raised questions about global language politics, foreign language expertise and education, and grassroots internationalist activism that the state could not ignore. Studying Esperantists means examining not only the global-mindedness of this distinct constituency in its evolving historical context, but also the wider frame of the language politics of imperial Russian and early Soviet internationalism.

Can you explain how your work challenges, differs from, or complements, other work in your field?

Within the specific frame of Russian and Soviet history, much of the pioneering work that has been done in the last decade on the study of internationalism has focused intensely on the Cold War period. Some exceptional work on early Soviet cultural diplomacy has also helped to transform the field by calling its attention to the transnational and international dimensions of Soviet social, cultural, and intellectual history. My book responds and contributes to those exciting historiographical conversations, but also seeks to push my colleagues’ attention to the history of internationalism in an earlier, pre-revolutionary period of Russian history as well.

The history of Esperanto as a global phenomenon begins with the history of the late Russian empire. To be more precise, it begins in the multilingual, multiconfessional western borderlands of a tsarist empire that was in crisis and trying to cope with the palpable demands of fin-de-siècle globalization. Although the Esperanto movement came to be associated with its organizational centres in western Europe, Esperanto excited the imaginations of thousands of men and women throughout the late Russian empire who were aching to assert themselves as citizens of the wider world. Their Esperantist, internationalist version of “social daydreaming” (to borrow historian Richard Stites’ inimitable phrasing) was as much a response to their palpably globalizing world as to their local circumstances in a Russian empire undergoing rapid socioeconomic, cultural, and political change. Esperanto is an avenue toward better understanding the heightened global-mindedness of literate society in late imperial Russia and the creative approaches to living internationalism that men and women attempted in late imperial Russia and its Soviet successor.

What has been the most controversial aspect of your research?

I don’t think my work has been controversial so much as surprising for those of my colleagues who have never thought seriously about Esperanto or any other international language project. If they have considered Esperanto at all, many historians have written it off as a curiosity worthy of an indulgent footnote or, at best, a mere decorative reference point in their treatments of internationalism’s rise in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Yet while many today regard Esperanto as no more than an obscure historical artefact of a failed and wild-eyed utopian scheme, Esperanto was wildly popular in the early twentieth century and its adepts were sober and serious about their visions of a world made better and more harmonious by means of an international auxiliary language that belonged equally to all. Esperanto inspired (and, albeit to a lesser degree, continues to inspire) a diverse array of constituencies throughout the world to imagine new modes of communicating and cooperating across borders both literal and figurative.

Even more to the point, it has seemed that some of my colleagues have been surprised (pleasantly, I hope) to find that the history of Esperanto serves as a particularly productive way of exploring how “ordinary people” in late imperial and early Soviet Russia were reckoning with their own and their country’s place in a much wider world. Traveling to world Esperantist congresses, engaging in Esperantist pen-pal correspondence, hosting foreign Esperantist comrades, contributing to (and consuming) an international Esperantist literature, nurturing lifelong friendships with Esperantists one would likely never meet in person, and otherwise reaching out to the world and conversing with foreigners by means of an international auxiliary language were not politically neutral acts either before or after the October Revolution. This typically grassroots Esperantism reflected a popular self-consciousness of the “internationality” of a simultaneously hopeful and anxious era. Esperanto also contributed uniquely to the nature of late imperial Russia’s and the early Soviet Union’s relationships with the rest of the world.

What has been your proudest achievement to date?

I was honoured to have the opportunity to collaborate with the Reluctant Internationalists in organising the “Languages of Internationalism Conference” hosted at Birkbeck in May 2017. The Languages of Internationalism Conference brought together historians, linguists, and literature scholars to consider and debate how language complicated, facilitated, or otherwise impacted the pursuit and experience of internationalism in a diverse array of historical settings. The scholars who presented their work demonstrated just how central the question of language is to the history of internationalism. The conference also made apparent how the question of language diversity and language politics was a productive arena for thinking comparatively about internationalism in its wide variety of guises.

We considered the promises and politics of international language projects like Esperanto and Gestuno; the “hard” and “soft” power of language in the Cold War; the politics of language choice for local and transnational communication in the Jewish diaspora; and the global politics of language at the League of Nations, the United Nations, and the World Health Organization. We considered how the search for a shared language confronted fin-de-siècle Zionists, Catholic nuns, and cold-war era scientists puzzling over the meanings and nature of permafrost. The conference likewise explored the questions ignited by producing and publishing children’s literature for a global audience; the language politics of international feminist projects; and the understudied but essential role played by translators, interpreters, foreign language teachers, international press correspondents, and other experts and intermediaries tasked with making words, ideas, images, and culture intelligible across and beyond borders. As was demonstrated time and again at the conference, both the agents and targets of internationalist projects confronted the dilemmas and opportunities of language diversity time and again. Historians of internationalism cannot afford to overlook the very central politics of language in their studies.

Are there any aspects of your work that could be particularly relevant to scholars from other fields or practitioners in other areas?

My work pushes scholars of all fields to take seriously a central and persistent human problem that the Esperantists whom I study were trying to confront head-on: it is exceedingly difficult for people to cooperate or even simply to communicate on an international basis in the absence not only of a shared language, but also of a language that does not presuppose and reinforce hierarchy. Historians are keenly aware of the messiness of human life, of how realities are far more complicated than ideals. Even so, it is sometimes too easy —because of methodological blindness, silences built into the primary sources, and the onerous language demands made of scholars who study internationalism (to name just a few considerations)— for historians to overlook or consciously evade the messiness of language politics in their studies.

Histories of internationalism cannot afford to take the question of language for granted because our historical subjects could not afford to take it for granted. We need to ask: how were ideas being (mis-)communicated, if communicated at all, in the international conferences and organizations that began proliferating in the late nineteenth century? What strategies and technologies did internationalists adopt to help overcome the nagging “problem of Babel”? What can internationalists’ attempts to solve this problem tell us about the politics and the outcomes of their projects? How did language politics shape the experiences of men and women who attempted work across borders in pursuit of various internationalist aims? How did the politics of language create new opportunities for creative manoeuvre and personal or professional reinvention on local and global stages? How have the politics of language soured and helped to defeat even the most well intentioned efforts to cooperate on a global basis? How do past efforts to confront the global politics of language inform today’s internationalism(s)?

Where do you see your work going next?

Since I began working on this book, my historian’s imagination has “fireworked” in a number of related directions and sparked ideas for potential offshoot articles and subsequent research projects. For example, I’m interested in how the linguistic confusion and massive-time wasting that prevailed in the early Comintern helped to drive the early, albeit quite limited Soviet efforts to teach foreigners the Russian language as “the language of Lenin” and the lingua franca of international communism. I am also fascinated by the life stories—many of them little known, if known at all—of the foreigners who worked in the early Soviet Union as interpreters and translators (in the Comintern, the Foreign Languages Publishing House, VOKS, etc). Their expertise was in extraordinarily high demand, and they occupied a distinct niche within the Soviet Union and in interwar international communism more broadly. The majority of them were women. Without them, much of the quite elemental practice of early Soviet internationalism could not have been achieved.

In addition to these interests, I also envision a third book project that, in a highly unexpected way, was inspired by my research into Esperanto, language politics, and internationalism in late imperial Russia and the early Soviet Union. For now, I’ll keep that book idea to myself. Yet I will say this: as a citizen of the United States (and the wider world), I have experienced the past couple years as a time of particular anguish, anger, and disgust. For me as a historian, one positive outcome of my attempts to survive these times humanely has been that I am more than ever invested in pursuing women’s history research. If and when I write this third book that I currently daydream about, women will be at its very centre.

What would you like to ask the next person to be featured in this ‘spotlight’ series?

What practical advice would you give to an early doctoral student who wants to pursue a dissertation topic (no less than an academic career) within the frame of the history of internationalism?